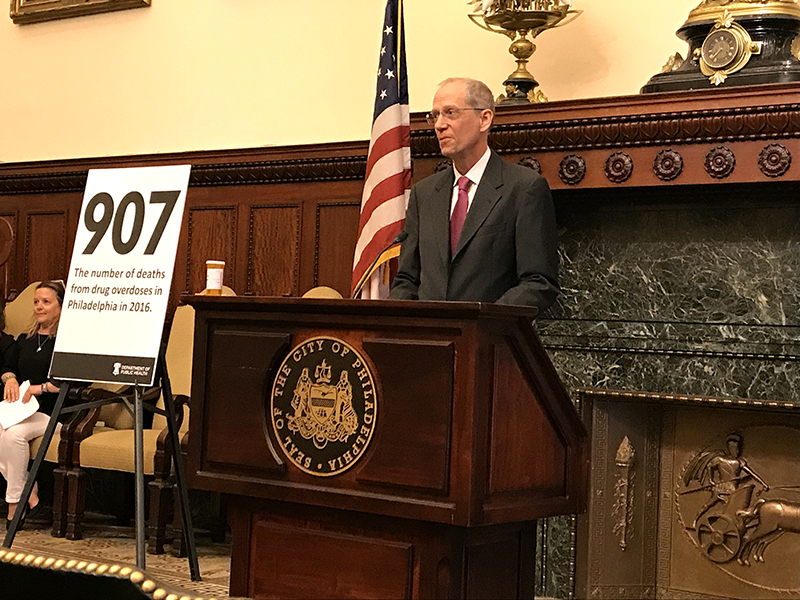

WHEN TOM FARLEY TOOK OVER as Commissioner of the Philadelphia Department of Public Health in 2016, the Philadelphia Business Journal labeled him an “out of the box thinker” based on his previous work in New York City’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. He is living up to the moniker with his recommendations to contain the opioid crisis in Philadelphia.

Farley completed Tulane medical school in 1981 and then earned an MPH in Epidemiology in 1991. He also served as chair of the Department of Community Health Sciences and was director of the Tulane Prevention Research Center.

“Desperate times force us to rethink our assumptions,” said Farley, about the opioid crisis. “In Philadelphia we had over 1,200 overdose deaths in 2017. That’s 30 percent more deaths in a year than we saw from the AIDS epidemic at its height.”

Overdose deaths in Philadelphia have also outpaced homicides, which are one-fourth the toll of opioids – and fatal overdoses are just the tip of the iceberg in representing the full impact of the opioid epidemic on the city. The city sees thousands of non-fatal overdoses annually, and an estimated 469,000 people received a prescription for opioids over a 12-month period. Approximately 6,000 people are in medication-assisted treatment in Philadelphia – and the city services could accommodate 2,000 more.

In response to the crisis, Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney convened a 23-member task-force which made 18 recommendations in areas of prevention, treatment, overdose prevention, and comprehensive harm reduction in 2017.

“Our response to this crisis has got to be multi-faceted,” explained Farley, who co-chaired the task-force with Arthur C. Evans, now the CEO of the American Psychological Association (APA) and formerly the commissioner of the Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Intellectual Disability Services.

Perhaps the most controversial recommendation is Farley’s advocacy for Comprehensive User Engagement Sites or CUES – locations where injection drug users can receive sterile needles, use drugs they obtain on their own under medical supervision, and also receive information about overdose prevention, addiction treatment, and recovery. These sites can also serve as a gateway to referrals for care for other problems, such as diabetes and mental illness.

Farley says that according to the task force’s estimates, safe injection sites could save up to 75 lives annually. Farley acknowledges that number may seem small in comparison to the overall toll of opioids – “but it’s not a small number if one of those lives is your son or daughter,” he pointed out.

“People will be able to come in to the facility, inject under supervision, and engage with people while they are there. This keeps them alive until they get into treatment,” he explained. “There are more than 100 such facilities all over the world.”

Members of the task force traveled to a facility in Vancouver, Canada, to see how it operates and speak with local community leaders. They prioritized speaking with law enforcement about their perceptions, which Farley argues was a crucial step towards encouraging local law enforcement to be open to CUES. Philadelphia has had clean needle exchange programs in operation since 1991, he pointed out, and has seen remarkable success in reducing the spread of bloodborne infections such as HIV as a result.

“Comprehensive User Engagement Sites also help the neighborhoods around them,” he said, explaining that in the neighborhoods that are most impacted by opioids in Philadelphia, people are often injecting in public. “With these facilities, that activity is out of sight, and there are fewer littered syringes on the ground. Evidence is strong for these sites. Based upon that visit, the city of Philadelphia has said we could benefit from a facility. But there are a lot of hurdles to overcome.”

Other strategies recommended by the task force include more oversight of opioid prescription practices, discouraging individuals from accepting opioid prescriptions, media campaigns addressing prescription opioids, making medically assisted treatment more available, enhancing housing options for people in treatment and recovery, and implementing substance use disorder assessment and treatment in the criminal justice system.

“We are also working to make naloxone more available. Our current recommendation is that any person in Philadelphia who knows someone using opioids should carry it,” said Farley.

Farley is also leading the charge to counter other chronic health problems in Philadelphia. He and his team have campaigns to reduce smoking and obesity, including working with the City Council to pass a tax on sweetened beverages. “We are seeing declines in obesity in children already,” said Farley.

However, the debate over how to effectively address the opioid crisis remains in the spotlight. “Opioids are the biggest public health crisis in a century,” he said.

— Madeline Vann (HEDC MPH ’98) freelance health and medical writer

RESOURCES